July 18, 2023

【教員インタビュー】目黒公郎 教授(後編)An Interview with Prof. MEGURO, Kimiro (Part 2)

目黒公郎先生のインタビューの後編です。今回は日本そして東京大学における地震防災研究の歴史から、防災に取り組む考え方や、「災害イマジネーション」の必要性まで広くお伺いしています。

In the second part of the interview, Prof. Meguro talked about the history of earthquake disaster studies in Japan, especially at the University of Tokyo, and about his general approach to disaster management. (前編はこちら/Continued from Part 1)

日本語は抄訳に続く(Japanese interview text follows English summary)

There was already some awareness of the need for research on earthquakes even before the magnitude 6 class Yokohama Earthquake in 1880. This event was the final straw that led to the creation of the Seismological Society of Japan — the world’s first academic association devoted to studying earthquakes — with nearly a hundred and twenty members including about 30 Japanese and many foreign scientists in Japan and abroad. Among the early members of the association was Kiyokage Sekiya, the first person in the world to be appointed to a professorship in seismology. The field of earthquake engineering began after the devastating Nobi Earthquake in 1891, in which many buildings were destroyed. After the 1923 Kanto Earthquake, building codes and other legal frameworks began to be established. The University of Tokyo was particularly strong in the field of engineering at the time, but the need for social and information studies for disaster management was increasingly recognized. The Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies (a predecessor of the III) played an important role in developing the latter. Furthermore, in 2008, the Center for Integrated Disaster Information Studies (CIDIR) was set up to promote cooperation among the different university departments, such as Institute of Industrial Science, III, and Earthquake Research Institute, concerned with disaster studies.

Only three years after the creation of CIDIR, Japan suffered the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster in March 2011, providing an urgent reminder of the need for continued work on all aspects of disaster management. Prof. Meguro points out the dangers of over-specialization which may lead to areas falling in between disciplines being ignored. A realization of this weakness has led to the formation of the Japan Academic Network for Disaster Reduction, which promotes broad collaboration among over sixty societies.

Since its foundation, CIDIR has continued to expand into new fields of disaster management research, working with additional university departments. In 2020, the Interfaculty Initiative in Disaster Recovery and Revitalization Research, with Prof. Meguro as its director, was established by the three departments that founded CIDIR and four new additional departments.

According to Prof. Meguro, Japan cannot afford to continue relying mainly on the national and local governments to provide disaster countermeasures. Effective disaster measures require a mobilization of society as a whole and a permanent state of grass-roots preparedness. Disaster measures should no longer be considered as a one-time cost but rather as the creation of enduring value in society enabling it to tackle disasters more effectively whenever they occur. Disaster countermeasures should be “phase-free” in the sense that their main purpose is to improve the quality of life in normal times besides also being used in times of crisis when a disaster occurs. Public authorities need to shift from the direct provision of disaster support to a policy of nurturing an environment in which businesses and individuals can carry out disaster countermeasures spontaneously.

In accordance with the idea of “phase-free”, Prof. Meguro advocates a lifestyle that does not require making special provision in case of a disaster. A survey by his laboratory has, for example, revealed that most Japanese households already stock about one week’s supply of food. If these existing food supplies can be used effectively, there is no need to make special provision for a disaster. With the right knowhow, a family can find ways to survive, so long they have enough drinking water and gas cartridges to power a portable stove.

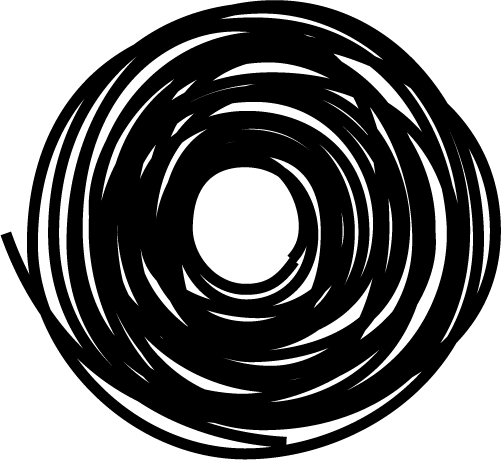

“Meguro Maki” is a tool for promoting such a lifestyle, and workshops using this tool are called “Meguro Maki Workshops.” The reason why it is called Meguro Maki is that a roll of paper, known as maki in Japanese, is used in the workshop. Many such workshops have been conducted with adults, students, and children to encourage the development of “disaster imagination.” The participants are presented with a specific disaster scenario and asked to create their own stories in that scenario. They fill in their own imagined stories on a timeline as the events unfold, detailing the problems they would face and how they would act in a disaster. When in doubt about what to do, they attach question cards. After writing the stories, participants are asked to show their stories to each other and compare them at the workshop session.

The scenario can be varied to encourage the target group to become aware of issues they had never considered before. For example, a workshop for local government employees was presented with a scenario in which an earthquake occurred at 5 p.m. on the eve of an election. This led to discussion about how citizens could be informed if the election had to go ahead as planned and what to do if the polling stations were also being used as evacuation sites. Meanwhile, in a workshop for students, participants because aware of the possibility of their own death in a disaster, leading to speculation about what would happen to their family and friends in their absence. This gave them a fresh appreciation of the value of their lives and the importance of reflection on how they themselves could contribute in a disaster situation.

There is much discussion about how to attend to the special needs of especially vulnerable individuals in a disaster, including the elderly, those with disabilities, pregnant women, infants, and foreign nationals lacking the ability to communicate in Japanese. Such people are sometimes referred to as “those requiring special assistance in a disaster”, and abled people think that they do not belong in this category. However, through the workshops, many people besides those belonging to such categories realize that they too could find themselves suffering disabilities or having special needs in a disaster scenario. They could, for example lose their spectacles or contact lenses, or they could be severely injured by falling debris or broken grass. Therefore, special needs are not a marginal issue only affecting specific groups but something requiring constant and universal attention. In this sense, it would be better to redefine abled people as “temporally undisabled”, thus allowing us to see the world differently. The whole point of “disaster imagination” is to develop preparedness for situations that would be unimaginable in normal times.

Prof. Meguro would like to invite all those interested in disaster research to join him in a great reform of disaster response strategies based on a highly developed disaster imagination and the two concepts of “value over cost” and “phase-free.”

Those who would like to learn more about “Meguro Maki” may refer to the following website: http://risk-mg.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/meguromaki/_src/1350/meguro_maki.pdf

– 2023年は、関東大震災発生から百年という事もあり、災害研究にも注目が集まっています。日本における防災研究の歴史の中で、東京大学はどのようにこれを展開してきたのですか。

1880年2月22日に横浜でマグニチュード6弱の地震(横浜地震)が発生しました。当時は日本に大勢のお雇い外国人たちが滞在していたわけですが、日本での地震の多さに驚き、地震を学術的に研究する必要性について、この地震の1年くらい前から議論をされていたようです。そのようなタイミングで、横浜地震が発生したので、それが最後の一押しとなって、同年の3月11日には、地震を研究対象とする世界で最初の学会「日本地震学会」が設立されました。会員数は120人弱、その中の日本人が30数名で、残りは国内外にいた外国人でした。有名なところでは、ジョン・ミルンやジェームズ・アルフレッド・ユーイングらがいました。彼らと共に研究をしていた日本人の中に、後に世界初の地震学の教授になる関谷清景やその後を継いだ田中館愛橘や大森房吉らがいました。

1891年10月28日には、内陸のM8クラスの地震である濃尾地震が発生し、7,000人を超える死者が出ました。多数の建物も被災したので、地震工学的な研究が始まります。そして1923年の関東大震災を機に様々な基準が設けられます。震度法という耐震設計法を考案した建築構造学の佐野利器、今も多く残る関東大震災の復興工事として隅田川に架かった橋梁群を設計した技術者の多くは本学の土木工学の教員や卒業生です。この頃の東京大学における防災研究は、ハード面(構造物の防災対策)の研究に特化していました。それから少しずつ、人文社会系や情報系の研究が加わってきます。文学部などでは、大地震を日本史の中のひとつの出来事として捉えますし、情報学環の前身である新聞研究所では、情報の側面から防災研究が行われるようになりました。

しかし個別の研究だけでは解決できない問題に取り組むために、2008年に、CIDIR(本学大学院情報学環総合防災情報研究センター)が、情報学環と地震研究所と生産技術研究所の連携によって設立されました。

– 東日本大震災が起きたのはCIDIRの設立から3年後だったのですね。

そうです。あの時に痛感したのは、我々研究者が自然の脅威というか、自然に対する畏敬の念や謙虚さが少し薄らいでいたということです。言い方を変えれば、自分たちの技術や知見、知識を過信、盲信していたということです。

防災の世界に限らず、研究を効率化しようとすると、分野を狭めて深堀りする方法が選択されがちです。能率がいいからです。しかしその結果、深堀と深堀の狭間に取り残された隙間ができてしまう。その隙間に関しては、「みんながお互いに誰かがやってくれるだろう、自分はやらなくてもいいかな」と思ってしまう。しかし、取り残された隙間に課題があって、それを原因として問題が発生し、それが繋がって大きな問題になったと思えることがいっぱいありました。その反省から、日本学術会議などに積極的に働きかけて、災害に関連の深い少数の学会の連携では解けない問題が多いので、「広くみんなで連携しましょう」と、62学協会をメンバーとする「防災学術連携体」を創設しました。

東大の中には、CIDIRで連携している学環・地震研・生研の3部局に加え、医学部附属病院、工学系研究科、農学生命科学研究科、アイソトープ総合センターに新たにメンバーになっていただき、2020年に私が機構長をつとめる「災害・復興知連携研究機構」を設立しました。この機構は、当初はCOVID-19の関係で、対面での活動が制限されましたが、「関東大震災から99年」の企画として、2022年に関東大震災を特集する3回の公開研究会を実施して好評を得ました。2023年は7月23日と30日に安田講堂で関東大震災100年の連続シンポジウムを行います。

– 最新の防災研究の知見から、具体的な防災への取り組み方などをお聞きしたいと思います。

現在の日本では、国家の存続さえも危ぶまれる規模の災害(これを国難級災害と呼ぶ)の発生が危惧されています。この代表が首都直下地震や南海トラフ巨大地震です。防災の担い手には「自助・共助・公助」の三つがありますが、従来は、国や都道府県・市町村が公金を使って実施する「公助」がメインでした。しかし、現在の少子高齢人口減少や財政的な制約を考えると、今後の巨大災害対策は「貧乏になっていく中での総力戦」を強いられる状況です。このような環境下では、従来通りの「公助」の割合を維持していくことは不可能です。この「公助」の目減り分は「自助」と「共助」で補うしかないわけですが、これまでのように、それらの担い手である個人や会社、NPOやNGOを含むグループやコミュニティーの「良心」に訴える防災は、もはや限界です。この状況を変えていくには、防災対策に対する意識を「コストからバリュー」へ、さらに「フェーズフリー」なものにしていく必要があります。従来のコストと考える防災対策は「一回やれば終わり、継続性がない、効果は災害が起こらないとわからないもの」になりますが、バリュー(価値)型の防災対策は「災害の有無にかかわらず、平時から組織や地域に価値やブランド力をもたらし、これが継続されるもの」になります。有事と平時を分けないフェーズフリーな防災対策は、平時の生活の質の向上が主目的で、それがそのまま災害時にも有効活用できる防災対策です。

これからは、上記の「コストからバリュー」と「フェーズフリー」に基づいて、防災対策のソフト・ハードを「防災ビジネス」として展開し、国内外に魅力的な市場を形成していくことが重要です。一方で、「公助」も質的に変わる必要があります。従来の行政が公金を使って実施する「公助」から、「自助」と「共助」の担い手が、自立的・自発的に防災対策を推進したいと思える環境整備としての「公助」への変質です。このようにしていかないと、我が国の今後の防災対は機能しなくなるでしょう。

– 先生ご自身は、防災対策としてどういった備えをされていますか?

私は、特別なものは備えてなくてもいい生き方を志向しています。それがフェーズフリーの考え方だからです。例えば災害時の食べ物。私の研究室で、各地の家庭を対象に、どんな食べ物が、どのくらい家に存在するのかを調べたところ、ほとんどの家には家族構成を考えても冷蔵庫や食器棚の中などに1週間分程度の食べ物があることがわかりました。これを循環しながら食べれば、災害時用の特別の準備は不要です。停電になったら、例えばお刺身はちょっと焼くとか、煮るとかすれば食べられる時間が長くなる。そういう工夫をすればいいわけです。

飲料水は足りないので、1人1日2リットルを目安に準備しておくことが大切です。料理も4人家族であれば6~8本のカセットを用意しておけば、卓上のガスコンロで1週間程度の料理が可能です。調理法としては鍋に風呂の残り湯をいれ、ビニールパックに入れた食材を湯煎で調理すると複数の料理を一度につくることができて効率的です。少し知恵を使えば、いろんな方法がありますよ。

-先生が取り組まれている「目黒巻ワークショップ」とはどういったものですか。

これは普段から災害を想像しておくこと、つまり「災害イマジネーション」を向上するワークショップのひとつです。この中では巻物のような用紙を使う「目黒巻」と呼ばれるトレーニングツールを使います。この用紙に、対象災害、月日と発災時刻、天候などを記載した上で、時間の経過にともって自分の周りに起こることを、自分を主人公とした物語として付箋紙に書いて、対応する時刻に貼り付けていきます。最初はなかなか書けません。分からないこともいっぱい出てくるので、疑問カード(別の付箋紙)に書き、対象箇所に貼り付けます。これをグループで行った上で、お互いの用紙を見せ合い、話し合いを行う。まず、自分の想像力の乏しさを実感すると思います。災害を他人事ではなく自分事として考えるきっかけになります。

一般的にグループでワークショップ(WS)をやるときは、組織の中でのリーダーや年配者など、声の大きい人が仕切りがちですが、目黒巻WSでは違う状況が生まれます。事前に目黒巻にいろいろと書いてもらい、WSの最初に相互にその内容を見せ合うわけです。すると、人前で積極的に発言するのが苦手なおとなしい人でも、そこにいいことが書いてあると、すごく尊重されます。一方で、声がでかくて偉そうだけどロクなこと書いてない人は、「あなたぜんぜん書けてないじゃないですか」と評価されるわけです。

WSを何度か実施できる場合は、特殊な条件でもやってもらいます。これは、設定した特殊な条件下で災害が発生すると言いたいわけではなく、特殊な条件を設定することで初めて気づくことがあるからです。例えば、市町村など自治体の方々を対象にしたWSでは、「首長の選挙の投票日の前日の夕方5時に地震が起こった」とする。そうすると、まず選挙を予定通りするかしないかをどうやって決定し、市民たちにどう伝えるんだっていうことからディスカッションが始まります。次は、避難所にみんな来るけど、選挙の投票所になっているのをどうするんだ、とか。ほかにも、1月1日の朝8時に起こったと設定したら、多くの職員が帰省して集まることができないけど、どうやって災害対策本部を立ち上げるんだ、というようなことが議論になります。さらには、人事異動の翌日に起こったと設定すると、引継ぎが不十分な状態で、どっちのポジションで対応すべきなのかなど、今まで考慮していなかったことが芋づる式に出てくる。気づきのきっかけになるということです。発災の時間帯を変えれば、自分の持つ役割の多面性にも気づかされるでしょう。

このワークショップを学生とやると、自分たちが死んでしまう状況があることに気づきます。そのような場合には、自分の死後の物語を書いてもらいます。自分が亡くなった状況を、家族や周りの人たちがどのように感じ、その後の人生を送っていかれるのかを物語として書いてもらうわけです。そうすると、自分が今までどれだけ多くの人たちの支援を受けて生きてきたのか、自分は死んじゃいけない存在であるのかなど、いろんなことに気づき、意識も大きく変わります。その結果、「防災対策をしなさい」などと一言も言わなくても、彼らは自分なりに考えて行動を始めるのです。防災対策は最大瞬間風速的に盛り上がってもだめで、継続性が重要です。なので、「災害イマジネーション」が不可欠なのです。

ほかにも「潜在的災害弱者」という考え方についてもよく話をします。通常、災害弱者とか災害時要援護者と呼ばれる人々は、高齢者や日常的に身体に障害のある方、妊婦さんや乳幼児、日本語によるコミュニケーションに問題のある外国人、などと定義されています。しかし、次のように考えるとどうでしょうか。例えば、「コンタクトレンズやメガネを使っている人が、激しい揺れの中でコンタクトレンズやメガネを紛失し、被災家屋の中でスペアが見つからない」、「揺れの最中に上から重いものが落ちてきて、頭部を負傷した。あるいは腕を骨折した」、「床に散乱したガラスや陶器の破片を踏み、足に大変な傷を負ってしまった」など。このような状況を前提にして、WSを実施してもらうと、直面する状況や自分ができることが大きく変わることに気づくでしょう。私たちは通常、自分を健常者だと思っていますが、「健常者は、今、たまたまハンディを持っていないだけの人(潜在的災害弱者)」と考えると見えてくる世界が変わります。「バリアフリーなんて自分とは関係ない、別世界の人の問題」などと考えていた人も、「ちょっと待って、福祉と防災を一緒にやった方が合理的ではないか」という話になる。こういった動機付けやきっかけ作りがとても大切だと思います。

人間は自分が想像できないことに対して、適切に備えたり、対応したりすることは絶対にできません。だからこそ災害イマジネーションが大切なのです。

以上のように、私の研究室では高い災害イマジネーションを持って、防災対策を取り巻く環境を、「コストからバリュー」と「フェーズフリー」という2つのキーワードの下、大きく変革していくための戦略研究をしているのです。そのためには、様々なディシプリンが必要です。これからの防災に興味のある方は、私たちと一緒に研究しませんか。

目黒巻についての詳しい解説と記入用紙については、こちらのURLをご参照ください: http://risk-mg.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/meguromaki/_src/1350/meguro_maki.pdf

企画:学環学府ウェブ&ニューズレター編集部

インタビュー:開沼博(准教授)・山内隆治(学術専門員)

構成:神谷説子(特任助教)

抄訳:デイビッド・ビュースト(特任専門員)

主担当教員Associated Faculty Members

教授

目黒 公郎

- 先端表現情報学コース

Professor

MEGURO, Kimiro

- Emerging design and informatics course